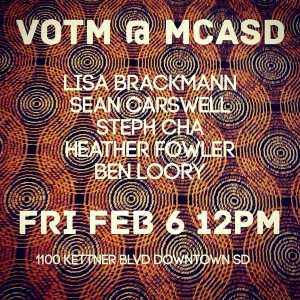

San Diego like I did. People spoke of him with reverence, yet I’d never met him. Finally, we had so many mutual friends that I emailed him and introduced myself. He was utterly friendly and suggested we get together for coffee and talk writing and what we were each working on. I got to meet his wife, Nuvia Crisol Guerra, as well, a creator of stunning and colorful paintings. I soon discovered the reason for the reverence when speaking of Jim Ruland is because of his own immense talent. I eagerly read Big Lonesome and had to cry after the first story. They were all dazzling. Because of our close proximity, I’ve had the pleasure of getting to hear Jim read at various venues in town, most especially for his own series—Vermin on the Mount (VOTM), one of the best reading gigs going on in San Diego and L.A.

San Diego like I did. People spoke of him with reverence, yet I’d never met him. Finally, we had so many mutual friends that I emailed him and introduced myself. He was utterly friendly and suggested we get together for coffee and talk writing and what we were each working on. I got to meet his wife, Nuvia Crisol Guerra, as well, a creator of stunning and colorful paintings. I soon discovered the reason for the reverence when speaking of Jim Ruland is because of his own immense talent. I eagerly read Big Lonesome and had to cry after the first story. They were all dazzling. Because of our close proximity, I’ve had the pleasure of getting to hear Jim read at various venues in town, most especially for his own series—Vermin on the Mount (VOTM), one of the best reading gigs going on in San Diego and L.A.

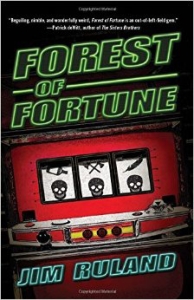

More recently I inhaled his newest book, Forest of Fortune, a fascinating characterization of Thunderclap, a fictional Indian gaming establishment outside of San Diego. The characters are edgy and raw with addiction, the plot requires you turn the page quickly to find out what in the world this group is going to do next, the language is exquisite and often hard-boiled.

Jim Ruland—”Writer. Sailor. Punk. Rat.”—is also the co-author with Scott Campbell, Jr. of Discovery Channel’s Deadliest Catch of Giving the Finger. He is currently collaborating with Keith Morris, founding member of Black Flag, Circle Jerks and OFF! on his memoir My Damage: 40 Years on the Front Lines of Punk, which will be published in the fall of 2016. He is the books columnist for San Diego CityBeat, and writes for the Los Angeles Times and Razorcake, America’s only non-profit independent music zine. His fiction and nonfiction has appeared in numerous publications, including The Believer, Esquire, Granta, Hobart and Oxford American, and his work has received awards from Canteen, Reader’s Digest and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Jim Ruland—”Writer. Sailor. Punk. Rat.”—is also the co-author with Scott Campbell, Jr. of Discovery Channel’s Deadliest Catch of Giving the Finger. He is currently collaborating with Keith Morris, founding member of Black Flag, Circle Jerks and OFF! on his memoir My Damage: 40 Years on the Front Lines of Punk, which will be published in the fall of 2016. He is the books columnist for San Diego CityBeat, and writes for the Los Angeles Times and Razorcake, America’s only non-profit independent music zine. His fiction and nonfiction has appeared in numerous publications, including The Believer, Esquire, Granta, Hobart and Oxford American, and his work has received awards from Canteen, Reader’s Digest and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Bonnie ZoBell: I know you worked in an Indian casino outside of San Diego as a copywriter. This type of huge establishment with an all-powerful management calling the shots often seems like some big dysfunctional family, probably worse since the rules are different in casinos. From what I’ve seen, there are a lot of bizarre, off-the-grid individuals visiting these properties, and the people who work there get to see them more up close and personal. Is this partly what made you write the book—the unusual characters?

Jim Ruland: Absolutely. I knew almost  immediately that I was going to write about my experiences at the casino. I’m also drawn to historical subjects, and the framework that created casino culture in the United States is pretty fascinating. Casinos attract people who are somewhat less risk averse than others so you get some interesting characters coming through the doors at all hours of the day and night. I think that also applies to the people who work there.

immediately that I was going to write about my experiences at the casino. I’m also drawn to historical subjects, and the framework that created casino culture in the United States is pretty fascinating. Casinos attract people who are somewhat less risk averse than others so you get some interesting characters coming through the doors at all hours of the day and night. I think that also applies to the people who work there.

BZ: Your three main characters couldn’t be more broken. You’ve got Alice, a woman who sees things and who could be, as she thinks, having visions, but who more probably is experiencing grand mal seizures, which causes her to lose jobs and sometimes herself. There’s Pemberton, an affable but not-so-recovering alcoholic and drug addict. And then there’s Lupita, a slot junkie whose family has disowned her. Did you always know these would be the main characters, or did they present themselves to you after you started writing?

JR: They emerged through the writing process. Alice was the first character I started to develop and it took about a year to get her voice right. Pemberton is the most autobiographical of the three main characters in that his situation mirrored my own as someone who had pretty good access to the casino but didn’t always understand what he was looking at. His development was voice-driven, too. Lupita’s character is probably a composite of the family I married into – a chaotic, sprawling Mexican-American family – and the fact that my fictional casino is located in San Diego near the border with Mexico.

BZ: I found your character Alice particularly poignant because she has no real addictions except for being so hooked on the idea that she’s not having grand mal seizures that she won’t try medication that might make her “visions” go away. She’s in such denial that she doesn’t want to explore the idea that she might have epilepsy, and then keeps finding herself in settings she doesn’t remember ever going to. What do you think admitting the possibility to herself would cause that she’s so afraid of?

JR: I’m fascinated by the power of denial, our ability to see what we only want to see. As a recovering alcoholic, I can see how warped my thinking used to be with respect to my addiction, but at the time I thought I was being very reasonable. Sometimes the most obvious truths are the hardest to see. For Alice, the trauma of her past keeps bleeding into the present.

BZ: And Pemberton is a pretty sad case. He gets thrown out of his L.A. apartment by his fiancé, drinks and snorts every cent he does or doesn’t have, and is so irresponsible that everyday his life is about to crack up even more than it already has. Can a man like this ever really be free of his addictions?

JR: Free? No. But if he achieves the clarity and confidence that comes with release from his demons, I think peace of mind is possible. At least that’s been the case for me. I wrote Forest of Fortune before I went into recovery and revised it afterwards, and that’s when I started to see the casino as a toxic place, at least for someone with addictive behavior and poor impulse control. I wanted to take Pemberton on the same journey that I was taking, but he’s trapped at the casino, and if he ever wants to be free, he needs to get out of the culture. That said, I love casinos!

BZ: I love multiple points of view in a book because it’s so illuminating to see how different characters view the same situation. Did you enjoy using it? What do you feel it allowed you to do in the book?

JR: I enjoyed it a great deal. It was kind of a breakthrough for me in that it allowed me to approach the novel differently. When you have a single protagonist, it’s fairly easy to slot him or her into a narrative situation. With multiple points of view, it was a lot trickier. The characters are beholden to themselves. They are driven by their own desires, especially in this book, which is all about desire. The first draft came very quickly, but it was very difficult to revise. I had to pull the story apart and revisit it through the lens of each character before braiding it back together. That took a lot of trial and error.

BZ: How much research was required to write this novel? Just because you worked in a casino doesn’t mean you automatically knew all the rules having to do with sovereignty or water rights or blood quantum—the amount of Indian blood a person must have to be eligible for tribal benefits. Did you have to research how different Indian casinos run their businesses and use their money to be able to create your fictional casino in this book?

JR: Not a lot. Although I was new to casino culture, my experience at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Arizona, served as an introduction to the Native American community, and I was exposed to the Navajo, which is the largest, poorest reservation in the United States. Many of my students and colleagues at the university came from the rez. When I went to work at the Indian casino in San Diego, I learned that there are over 550 Indian reservations with casinos, and that San Diego has the highest concentration of casinos in the country. Each tribe has its own story, and I’m intrigued by the ways they do or don’t use the casino as a means of telling it. I set up a bunch of Google alerts for casinos that always seemed to be in the news for the wrong reasons, and I learned some reservations were riddled with crime and corruption. The issue of tribal disenrollment is particularly galling to me.

BZ: Thunderclap isn’t a particularly good example of a well-functioning casino. Do you think most casinos are run like this and have the same problems? How is Thunderclap different than a contemporary casino that might be better run and benefit the Native Americans it serves?

JR: I had the misfortune of working in the casino industry during the recession. The gaming industry saw the recession coming sooner than most because we saw the needle moving in the wrong direction: people stopped spending money at casinos. It peaked when gas prices in California were at their highest and casinos are generally located in places that are a bit off the beaten path. It was a perfect storm of catastrophic economic indicators. It was a bad time for the industry. A lot of smart, hard-working people were fired. I think Thunderclap reflects that reality as opposed to making a statement about casinos in general.

BZ: What are you working on now?

JR: I’m working on a bunch of things. I’m getting started on My Damage with Keith Morris about his life as an L.A. punk rocker. I’m also finishing a new novel that’s a near-future quasi-dystopian story set in Los Angeles and revising a speculative short story collection inspired by my adventures in pet sitting, which is a fancy way of saying I wrote a book about cats.

[…] Skirt productions interview with the author Bonnie Zobell interview with the author The Nervous Breakdown self-interview with the author Santa Fe Reporter interview with the […]