From Gently Read Literature Spring 2014

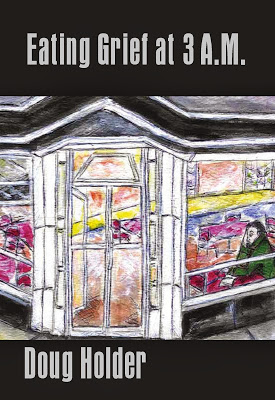

In the spare yet rich poetry of Doug Holder‘s book Eating Grief at 3:00 AM, published by Muddy River Books, there is a symphony of voices, places,

and sounds. So clear are the ambiences, the run-down settings, the often broken, yet not always unhappy people who populate these poems, it’s as if you’ve read a novel.

and sounds. So clear are the ambiences, the run-down settings, the often broken, yet not always unhappy people who populate these poems, it’s as if you’ve read a novel.

You haven’t, but the expanse of details encases us in thoughts and a story much bigger than some novels do. There are so few words used in this spectacular chapbook counting them wouldn’t take long, and yet they create worlds. For example, in the poem “Carpal Tunnel Syndrome,” we’re told:

I thought of my father

As he gripped

His left hand

Prying it open with his right

A hand curling

Into a callused fetus

Holding on to

Something

For dear life.

I know that man, though I’ve never met him. His tension, his frustration, his buried anger at himself and at others make me twitch. That grip makes him too uncomfortable to want to be around, and yet the idea he has to hold on so hard to keep it all together makes me want to rescue him. There are only 31 words in that stanza, and yet I am able to fully appreciate the man.

I know that man, though I’ve never met him. His tension, his frustration, his buried anger at himself and at others make me twitch. That grip makes him too uncomfortable to want to be around, and yet the idea he has to hold on so hard to keep it all together makes me want to rescue him. There are only 31 words in that stanza, and yet I am able to fully appreciate the man.

Holder’s ability to create such depth of character, to show such fully-wrought human beings with his sparse and yet impeccable lexicon is enough to make any novelist envious. In “Father Knows Best-Mother Does the Rest,” anybody who is ever watched the TV show—and many of us saw a whole generation’s worth—will know the essence of this character in the first few words:

The bland tyranny

of the cardigan sweater.

His smile

creased in brutal condescension.

Holder’s ability to portray a sense of place might be even stronger. Consistently throughout these gems the reader feels the setting and its meaning immediately. In “Transcendence,” we’re told:

I’m 84 floors up

but the city

only seems to

make sense

from my exalted omnipotence.

So many of us who’ve lived in large urban centers have felt reduced by circumstances and the anonymity that living among great masses can bring.

The old men leftover from bigger days who live in the heart of so many of our cities are elegantly depicted in “Eating Grief at Bickford’s,” a poem dedicated to Allen Ginsberg:

There are no places anymore

Where I can sit at a threadbare table

Pick at the crumbs on my plate . . .

The old men

Who used to spout

Marxist

Rants from

The cracked porcelain of their cups

Are gone

The boiling water

Ketchup soup

The mustard sandwich

These used to relish

Throughout this collection of a time gone by, there is a sense of a whole nation of people who used to be the carriers of big ideas and ideals, people we may see ourselves as today. Only that older set of folks are in the margins now, hidden in the crevices. Younger people march into bars and cafes, pass them on the street, and don’t even see those older humans, so sure are they of their own omnipotence, of their own starring roles. A past art teacher from one of the narrators’ third grade classes worked hard all her life and is now reduced to being an old, angry woman painting caricatures of angry old women, something a younger person finds completely irrelevant. A man thinks back to one of his many trips to Kentucky Fried when he tried to put the brittle-boned, old chicken back together again but now understands you can never put the bird together again for all we are are bones.

Humor abounds in these poems filled with people who aren’t always at the top of their game. This and the alluring use of language allow us to travel the depths of some of these narratives

Leave A Comment