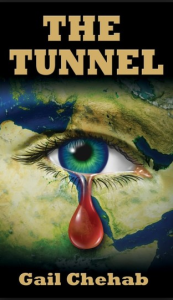

you to a whole new world, unless you’ve already lived on the Gaza Strip right before the Arab Spring. Many of us only think about this region when we see the news. Chehab’s richly-drawn book, though, gives us front row seats as a revolution is going on, and we follow and get wrapped up in the desperate life of the Hamdan family who live there. Endless bombs drop as this family and their neighbors try to exist. The sensory details are so excellent you may find yourself ducking for cover or waving to keep the smoke out of your eyes. The book trailer is scary!

you to a whole new world, unless you’ve already lived on the Gaza Strip right before the Arab Spring. Many of us only think about this region when we see the news. Chehab’s richly-drawn book, though, gives us front row seats as a revolution is going on, and we follow and get wrapped up in the desperate life of the Hamdan family who live there. Endless bombs drop as this family and their neighbors try to exist. The sensory details are so excellent you may find yourself ducking for cover or waving to keep the smoke out of your eyes. The book trailer is scary!

Through Chehab’s masterful writing, she humanizes the Palestinian conflict as one family struggles to survive under harrowing circumstances. Hemmed in on all sides, the Hamdans struggle as they live under occupation by the imposed Israeli embargo. Omar Hamdan, beloved father and husband and a devoted family man, begins digging an underground tunnel from Gaza to Egypt to smuggle in every day necessities. As if that isn’t enough, the Hamdan’s daughter, Hanan, is diagnosed with leukemia. The family is determined to save her. Hanan’s mother, Fatha, virtually falls apart at the news and begins drinking. Hanan’s brother, Khaled, can’t accept it and even thinks he’s to blame for some of the problems that come up. Is it possible for them to smuggle the very sick Hanan through the tunnel to the Egyptian hospital that can help her, not once but multiple times, without getting caught?

Gail Chehab’s first novel, The Echo of Sand, won the First Series Award for the Novel at Mid-List Press. Her latest novel, The Tunnel, was a finalist for The Arthur Edelstein Prize, a semifinalist for William Faulkner-William Wisdom Competition, Salem College’s International Literary Prize, and for the Ruth Hindman Foundation and University of Alabama Short Story Contest. Based on this novel, Chehab also received a fellowship from the Summer Literary Seminars in Lithuania and Kenya, and was awarded second place in The Roanoke Review Fiction Contest, in which the first chapter of The Tunnel was published. Chehab’s works have been featured and recognized by numerous publications and literary organizations, which include Ohio State University’s The Journal, The Briar Cliff Review, Carve Magazine, Cutthroat Magazine, South West Writers, Santa Fe Writers Project, Chautauqua Literary Journal, New Millennium, New York Stories, San Diego Book Award, and the Pacific Northwest Writers Association’s awards. In between writing, Chehab has undertaken various missions to Central America to provide free medical care to hundreds of working-horses and street dogs. She also volunteers at a therapeutic riding center where she assists children and adults with disabilities. She peacefully resides in the Cascade Mountains with her family.

Bonnie ZoBell: Omar Hamdan’s tunnel to smuggle black market goods into the Gaza Strip is so wonderfully detailed—the dankness and darkness, the danger they pose if Omar or any of the his traders are caught. Are these tunnels still in existence? What would have happened to the builder of one of these or anyone caught inside during the Arab Spring? What about now?

Gail Chehab: The tunnels in the Gaza Strip are a fluid situation. Periodically, they’re closed or destroyed, but new ones are dug as the tunnels are a source of livelihood for the residents of Gaza. They’re used to smuggle a wide range of goods, including livestock, food, medicines, clothes, car parts, and building supplies. Some are said to be used by militant groups to bring in arms and money. Recently, Egypt imposed a maximum penalty of life in jail for people who dig and use cross-border tunnels.

Gail Chehab: The tunnels in the Gaza Strip are a fluid situation. Periodically, they’re closed or destroyed, but new ones are dug as the tunnels are a source of livelihood for the residents of Gaza. They’re used to smuggle a wide range of goods, including livestock, food, medicines, clothes, car parts, and building supplies. Some are said to be used by militant groups to bring in arms and money. Recently, Egypt imposed a maximum penalty of life in jail for people who dig and use cross-border tunnels.

BZ: The story of Omar’s daughter Hanan is so poignant to begin with, the discovery that she has leukemia. But coupled with the fact that she lives inside a war zone and not near any hospital that can help her unless she can be smuggled to another country, is almost too much to bear, especially after you developed her so well and allowed the reader to grow fond of her. What are the survival rates of children with leukemia in the U.S.? How much does it go down in a third-world country? Was it hard for you to write this?

GC: Survival rates depend on the type of childhood leukemia. For example, the five-year survival rate for children with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) is now more than 85 percent overall. The five-year survival rate for children with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is now in the range of 60 to 70 percent. Five-year survival rates for children with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is between 60 to 80 percent. Of course, the outlook for each child is different, depending on a number of things such as prognostic factors.

There are no statistics available of the survival rates in developing nations. However, I assume the survival rates are much lower as treating leukemia, or any cancer, is very expensive and requires advanced medical technology, which is not usually available in developing nations.

Writing The Tunnel was the most difficult and rewarding experience of my life. The story is based upon a personal journey taken with my family to battle leukemia. I wrote the story when someone I loved was being treated for a bone marrow transplant. Isolated for many months in a hospital room, I wrote feverishly to keep my sanity. When we left the hospital, I kept writing and revising the novel. Every word was important as it was my therapy and a way to heal. I experienced migraines and nightmares as the words brought my true emotions to the surface. Now that the book is finished, I realize that it was a very important book to me. It enabled me to process a very traumatic period of my life and most importantly to raise the awareness of childhood cancer.

BZ: Your characters are well-drawn and -differentiated. You do a good job of showing their flaws even though we grow to care a lot about them. Khaled and his struggle became very poignant to me. Could you talk about him a little?

GC: Khaled is a fourteen-year-old boy who has the incredible opportunity to save his sister’s life with the possibility of becoming her bone marrow donor. However, this blessing turns into a burden as he no longer feels like a super hero, but a super demon. What if he is a match and the transplant doesn’t work? What if his sister dies with his bone marrow inside her? At fourteen, Khaled struggles with the idea that he not only has the ability to save, but also to kill his sister. Being a bone marrow donor at any age is one of the most rewarding experiences, but it can also carry some very heavy psychological issues, particularly for related donors.

BZ: The family deeply loves Haman. It’s heartbreaking to watch them go through this nearly impossible situation with her illness. The whole story is really about the human beings in it, though you also do a great job of highlighting this war and making it clear how serious childhood leukemia is. Any advice to other writers about how to manage this balance? How does one stay focused on the characters at hand while still making the points you want to make about the world without hitting the reader over the head?

GC: Great question as there is a delicate balance to humanizing a story and bringing in the environmental factors that affect our lives. When I started to write the Hamdan’s story, I knew I couldn’t write only about cancer. It would be unrealistic as we all have things occurring simultaneously in our busy lives. Cancer does not wait for us to say, “Okay, I’m ready now,” and it doesn’t knock and ask if it can come in. It just happens along with everything else, including school, work, and vacations. So how did I develop the characters and balance all the details? I looked at writing like painting in oils on canvas. You start to lay the basics or the understory, which is the cancer, and then start to build layers with a lot of rich detail that makes the story more complex. In The Tunnel, I had the premise of cancer, but I needed something more. The subject of war came to me when I was living in San Diego. At a children’s hospital, I met families who had a lot going on in addition to their child having cancer. I met single mom’s supporting their families, and caring for their child with cancer. I met military personnel who were serving in Iraq and Afghanistan while their kids were being treated for cancer back home. They had so much on their plate, but I was struck by their determination, hope, and faith not to give up. I think they clearly understood that life happens and it won’t slow down for our tragedies so we have to push forward. In truth, I didn’t think I could write a story just about cancer. It had to be layered with love, fear, and even death.

BZ: The Hamdans are so family-oriented and concerned about each other, and we see virtually no arguing or teenage angst as we would in most American families—maybe a little in Khaled when he’s having trouble accepting his sister’s disease and wants to feel independent enough that he can help. Do you think this is a difference in cultures? Or is because they’re living under such awful circumstances with a child who is terminally ill they just can’t afford to have fissures in the family?

GC: I believe that family squabbles become minimal when a loved one is very sick. Families tend to come together and put their personal differences aside when experiencing grief. In different cultures, love will always be love and death will always be death.

BZ: What are you working on now?

CG: Thanks for asking, Bonnie, as I’m very excited about my next novel, which should be finished by the end of the summer. A few years ago, I had the opportunity to travel to Cuba with my elderly mother on a People-to-People tour. We were touched by the warmth of the Cuban people, the depth of culture, and the painful separation of families. This unforgettable experience influenced me to write On the Island of Sugar and Secrets.

At fifteen, Elliot Chan is one of the abandoned. After his mother left him to save street dogs in Crimea, he is chosen for his immense talent to the play the cello at Carnegie Hall. Yet the opportunity for greatness turns to terror as Elliot is placed under investigation for a horrific crime at his Carnegie Hall debut. Along with his grandmother, they flee to Cuba to find her first husband, a lost love, after being separated by 50 plus years of embargo. But Elliot must risk a great deal—in fact he has to leave behind everything he loves—in order to save himself. On the island, Elliot’s exiled grandfather, a former dissident turned hustler, manufactures medicine producing animals that seem like science fiction. He fights his captivity by acting crazy as deception is more powerful than the gun. Fear turns to wonder as Elliot disappears into a netherworld of spies, fugitives, mojitos and smoking hot women. From Canada to Carnegie Hall to Cuba, it would take another revolution to make up Elliot’s adventures. Captured by a tragic beauty, he is certain he ceases to exist and then miraculously reinvents himself. The Island of Sugar and Secrets is a testament that explores the generosity of love and a journey that maddens, toughens and restores a teenage boy who grows up.

BZ: Great talking with you, Gail! Can’t wait to read this next one.

Leave A Comment