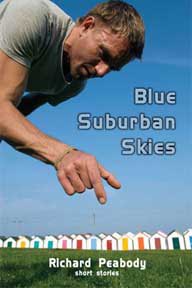

ichard Peabody is author of the recent collection Blue Suburban Skies, published by the Mint Hill Books imprint of Main Street Rag, and the forthcoming The Richard Peabody Reader, edited by Lucinda Ebersole and published by Alan Squire Publications with SFWP. He’s the founder and current editor of Gargoyle Magazine and editor (or co-editor) of twenty-two anthologies including Mondo Barbie, Conversations with Gore Vidal, and A Different Beat: Writings by Women of the Beat Generation. The author of a novella, two other short story collections, and seven poetry books, he is also a native Washingtonian.

He won the Beyond the Margins “Above & Beyond Award” for 2013.

ichard Peabody is author of the recent collection Blue Suburban Skies, published by the Mint Hill Books imprint of Main Street Rag, and the forthcoming The Richard Peabody Reader, edited by Lucinda Ebersole and published by Alan Squire Publications with SFWP. He’s the founder and current editor of Gargoyle Magazine and editor (or co-editor) of twenty-two anthologies including Mondo Barbie, Conversations with Gore Vidal, and A Different Beat: Writings by Women of the Beat Generation. The author of a novella, two other short story collections, and seven poetry books, he is also a native Washingtonian.

He won the Beyond the Margins “Above & Beyond Award” for 2013.

Bonnie ZoBell: Hey, Richard. Thanks for agreeing to answer some questions about Blue Suburban Skies. One of the things I most appreciated at the beginning your book were the stories narrated by fathers of young children. They were very well done, and I especially appreciated that you didn’t get all cutesy about it. These stories are striking and have good conflict, yet there is also fatherly affection throughout. Do you have trouble walking that line—writing about children in adult stories without getting too adorable about it? Any tips for other writers?

Richard Peabody: I’m sure my daughters wouldn’t agree with you. Ha Ha. I like to think as a late blooming first-time father that I have a slightly different perspective. My leap from knowing almost nothing about kids into becoming a stay-at-home father was a crash course in absurdity. Everything I knew about kids before that was due to my own Peter Pan existence. I like to think I’m more patient now. I also feel like children are invisible to people without kids. At least for me. (Unless you’re on a long distance flight.) Once I had a kid of my own, snap, there were playgrounds and kids all over the place. My focus had been elsewhere. A sort of blindness. But then I used to give copies of Christina Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children to those about to get married. As a goof. My getting married was a definite sign of the Apocalypse.

Richard Peabody: I’m sure my daughters wouldn’t agree with you. Ha Ha. I like to think as a late blooming first-time father that I have a slightly different perspective. My leap from knowing almost nothing about kids into becoming a stay-at-home father was a crash course in absurdity. Everything I knew about kids before that was due to my own Peter Pan existence. I like to think I’m more patient now. I also feel like children are invisible to people without kids. At least for me. (Unless you’re on a long distance flight.) Once I had a kid of my own, snap, there were playgrounds and kids all over the place. My focus had been elsewhere. A sort of blindness. But then I used to give copies of Christina Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children to those about to get married. As a goof. My getting married was a definite sign of the Apocalypse.

“Adorable” can be a trap. My girls are teenagers now so it’s pretty much scorched earth around the house. Easier to look back on when we were exhausted and the kids were way cute. In the stories you mention I kept the children to the periphery. The teenager in the title story never appears. The reader learns about others, hears their voices, views some of their interactions. I think I’m becoming more comfortable with including them now, and I think that’s what you’re referring to. A particular comfort level. No real tricks to it. I try to render some combo of my own remembered childhood and the daily pulse of my kids’ lives. I guess in a way my focus remains elsewhere, but children are along for the ride for now. And in the last story the teenagers take over.

BZ: A father with young children seems like a different kind of theme and narrator than I’ve read in a while. Do you agree, or have I been reading too many books by women and missing this? If you feel like there are others writing about this, could you name a few?

RP: I just discovered that Nathaniel Hawthorne kept a stay-at-home dad diary. Twenty Days with Julian and Little Bunny by Papa.(Of course he was married to one of the Peabody sisters.) Fathers seem to be a huge market right now. I thought I was a male Anne Lamott and shopped a book about my first year or so entitled “Twyla Tales: Confessions of a Rookie Dad,” but nobody ever bit. The past decade has birthed a lot of nf/memoir Daddy books. Dave Engledow’s Confessions of the World’s Best Father has humbled me. I also love Ben Tanzer’s Lost in Space: A Father’s Journey There and Back Again,” and he’s also part of Four Fathers, a book he co-authored with Dave Housley, among others.

I don’t see a lot of children in most of the fiction submitted to Gargoyle. Women, of course, do it all of the time. Could be guys are afraid to follow suit? Dunno. I will say how surprised I was when I read Hemingway’s Islands in the Stream and found him writing about a father and children in the first third of the novel. An entirely different focus for him. Would have been interesting to see what would have happened if he’d kept at it.

Oh, I’m a big fan of Ron Koertge’s YA novel The Arizona Kid. My daughters want me to write dystopian YA, but I think it more likely my 14-year-old will. Best thing of all is trying to create a story that operates on several levels so that adults and kids can both read it and get something different out of the experience.

BZ: Later in the book the subject matter shifts. It’s always interesting to me how writers decide to order their collections. How did you organize Blue Suburban Skies?

RP: Scott, from Main Street, didn’t want me to open with “Bottom Feeders . . . ,” which is how it was set up. As though the book was one long hallucination. I didn’t want the title story to lead. So “Bottom Feeders . . .” traded places with “A Great Big Smile on a Little Bitty Girl.”

I wanted a mix of Delmarva settings interspersed with more far-flung US stories—Woodstock Woodstock, Taos, New Orleans, Charleston, and North Carolina. I wanted a mix of outsiders in first and third POVs. The Nantucket Sleighride of the last 4-5 stories was intentional. Fire, dementia, violence. To my surprise the stories that have resonated the most with readers are the ones featuring Renfro, Wyatt, Eddie Luhan, and Isabelle. Not at all what I would have predicted. There’s a conspiracy afoot to make me write more about Eddie Luhan in Taos.

BZ: The range of your writing in this book is also impressive. Further in, the story you just mentioned, “Bottom Feeders and Prospective Memory,” is narrated by a woman—which you do a good job with. This piece has equal parts whimsy (mermaids) and pensiveness as we know there is something wrong with this woman as she keeps needing to take codeine and having seemingly important memories about the past. For some reason, my guess is that she has cancer, partly because the dog’s name is Chemo, but maybe it doesn’t matter what she has. Do you enjoy doing this in your writing—putting serious content together with magic? Would you call this magical realism?

RP: The artist is hurting but Tom is the one with cancer. She’s part creating, part grieving in advance. Sometimes I believe it’s just dumb luck. But since I’ve taught a lot of experimental fiction writing classes perhaps it just creeps into everything I do? Or maybe it’s just leftover from the 60s? I do try to add magic because most American writers don’t. Writers in my classes tend to be polarized into the realism camp or the experimental camp. I like forcing them to break bread together. That said, I’ve had some fabulous students who love to experiment—Rae Bryant, Julia Slavin, Dave Housley, Matt Kirkpatrick, and lots more.

“Bottom Feeders…” was one of those stories that didn’t work until I flipped the gender. The artist made a lot more sense as a woman. Everything fell into place. Artists are magical to begin with. Or maybe writers are just jealous because artists, dancers, composers, musicians, have different operating programs that look so appealing after sitting at a desk for a few days? The grass is always greener.

BZ: What would you do if you were having a calm, relaxing swim and ran into a mermaid?

RP: Ahh, then I would be William Powell in Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid. Not too shabby. Though both of my daughters watched that Australian TV series H20 about present day mermaids and that’s probably why I had mermaids on the brain.

BZ: A few stories later, “Dresden for Cats” introduces the seriously eccentric Uncle March, a man who was known in his earlier years as a genius composer. Somehow in his later years he’s ended up on a ramshackle old farm where he’s built an entire city for cats in the barn. His wife is even more eccentric, and therein lies the poignancy. We’re able to laugh at her—we see some of ourselves in her, too—but she also has some kind of dementia, which makes the reader realize a whole lot more about Uncle March. He’s not just a kooky old uncle who the family has written off; he’s also a highly-sensitive man taking care of a woman in the middle of nowhere who has even more problems than he does. This is what I love about your writing, the way you’re not afraid to let us laugh at things in the world that are also sad, but you also don’t shy away from the serious elements in the tale. Is this something you strive to do in your writing?

RP: Thanks for the kind words. At poetry readings I always mix-it-up, so the audience laughs some, maybe gets emotional. That’s calculated on my part. Though often it’s a buzz kill. I know the original story idea sparked because a friend had a pile of organ pipes on his porch, and I’d visited a house near Cambridge, MD, that had a private graveyard. An earlier version was even darker. I’m just more relaxed and accepting re. my life and work these days. Finally! Nothing left to prove. Took me a long time to gain any sort of perspective on death, loss, and the sad yet often comic aspects of life. Uncle March and the cats give the story a different sort of spin. At least that’s what I was after. Though one is left to contemplate how a soundtrack of cats playing piano would work against the backdrop of a burning barn.

BZ: What are you working on now?

RP: I’m writing a novel that dips into mentorship, Homer, Greek myths, and “who dat” that actually wrote The Odyssey. Meanwhile, local indie Alan Squire Publishing, is assembling “The Richard Peabody Reader,” a sort of Best Of a la the old Viking Portable series (Conrad, Crane, et al.). Not that I’m on that level. Still, the idea of having the best of my existing work—poetry, fiction, and nonfiction—gathered in one thick book is appealing, particularly since so many of my previous publishers are defunct. That’s due out in 2015 in time for the AWP in Minneapolis.

BZ: I’ll look forward to reading that, too!

Very candid answers to excellent questions, enjoyed knowing more about Richard Peabody who gives so much to the literary world.

Thanks, Susan. He was a lot of fun to interview!