Cris Mazza and I aren’t sure how we first met. My guess is it was when we were both undergraduates at San Diego State University. Then we were both adjuncts and taught honors courses at San Diego Mesa College. We both love dogs. However our friendship first started, though, we’ve known each other for a very long time, both grew up in San Diego, California, and our lives have continued to cross paths as she comes to visit family in San Diego, as I travel through Chicago where she now teaches and read with her, at AWP, and so on. When I heard about her new book, I couldn’t wait to read it.

Cris Mazza and I aren’t sure how we first met. My guess is it was when we were both undergraduates at San Diego State University. Then we were both adjuncts and taught honors courses at San Diego Mesa College. We both love dogs. However our friendship first started, though, we’ve known each other for a very long time, both grew up in San Diego, California, and our lives have continued to cross paths as she comes to visit family in San Diego, as I travel through Chicago where she now teaches and read with her, at AWP, and so on. When I heard about her new book, I couldn’t wait to read it.

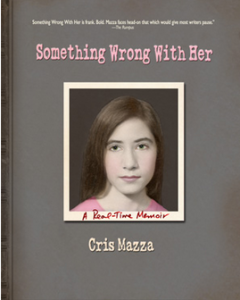

Cris Mazza’s most recent book  is a real-time memoir titled Something Wrong With Her. She has sixteen other titles including her latest novel Various Men Who Knew Us as Girls, re-released with a new foreword in 2014. Among her other novels and collections of fiction are Waterbaby, Trickle-Down Timeline, and Is It Sexual Harassment Yet? Her first novel, How to Leave a Country, won the PEN/Nelson Algren Award for book-length fiction. She has also been an NEA fellow and won 3 Illinois Arts Council literary awards. In addition to fiction, Mazza authored an earlier collection of personal essays, Indigenous: Growing Up Californian. Currently living 50 miles west of Chicago, she is a professor in and director of the Program for Writers at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She can be found online at www.cris-mazza.com

is a real-time memoir titled Something Wrong With Her. She has sixteen other titles including her latest novel Various Men Who Knew Us as Girls, re-released with a new foreword in 2014. Among her other novels and collections of fiction are Waterbaby, Trickle-Down Timeline, and Is It Sexual Harassment Yet? Her first novel, How to Leave a Country, won the PEN/Nelson Algren Award for book-length fiction. She has also been an NEA fellow and won 3 Illinois Arts Council literary awards. In addition to fiction, Mazza authored an earlier collection of personal essays, Indigenous: Growing Up Californian. Currently living 50 miles west of Chicago, she is a professor in and director of the Program for Writers at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She can be found online at www.cris-mazza.com

§

Bonnie ZoBell: At the beginning of Something Wrong with Her, you write about being in a band in high school and then college, which was the period during which you met Mark. You put a lot of time into that field. Did you ever consider majoring in music or going into that field? Do you ever play music anymore? Why or why not?

Cris Mazza: Band fed my need to belong to something where a community works together for a common goal. Also, since it was competitive (in high school), it fed that basic urge as well. I would have wanted to be in team sports if I was bigger. I played junior varsity softball, and if you knew how rinky-dink that was, you’d know it doesn’t count. (A dirt field, no uniforms except our gym clothes, etc.) Band was the big leagues of high school competition. In college it was another way to be involved, working toward a common goal, with a smaller crowd than the whole 30,000 — student campus. A ready-made group where my participation was welcomed and a role immediately waiting for me to fill (as opposed to how it might feel to join a club). Then working in the band office for the two directors was very much a way to feel needed, to find an identity where I had a role. I knew I wasn’t good enough to be a music major and never regretted that solid knowledge keeping me from making yet another career mistake. (I majored in journalism and never worked as a journalist, got a teaching credential and never pursued secondary teaching.) It wasn’t music that was important but the group goal. All of this — especially the needing to belong to a group part — would seem to go against my adult anti-social self, where leaving home for anything besides work obligations is somewhat of an ordeal and seems pointless. In high school and college, when I lived with my parents, I didn’t necessarily crave to always be at home, where the “role” I had to play was not one I wanted anymore.

BZ: You mention here and there that the band members were nerds. Are all band members nerds or are there cool ones, too? What were you?

CM: From the book: “The ‘band geeks,’ sharing our level of exile, devised our own social order and hierarchy, from the lusted-after ‘Banderettes’ who wore tight stretch pants or cheerleader-style miniskirts in front of the band, to the elite in the jazz ensemble and pep band, to the rowdy masculine trombone players, through the ranks of the talented and pretty and coolly radical, down to the nerds, the overweight, the hopelessly immature, or the dweeby freshmen.

I took on a leadership role and also adopted an instrument traditionally played by boys, so basically I was “one of the boys” and also a low-level leader. I felt at the time this removed me from being considered a desirable female, which I was both thankful for and frustrated by because I both chose it for the safety but also felt mostly left out of the bonding rituals. So my being left out or “not chosen” was only partially because I didn’t have the ideal-female characteristics determined by our culture; it was also largely my own fault in ways difficult to articulate in a short answer.

BZ: People may not realize until reading the book how interesting the structure is. There are letters back and forth between you and Mark over the years. There are excerpts from some of your works of fiction in which you were dealing with some of the issues you admit were autobiographical in this memoir. There are musical words and theories that you apply to your writing and to this book. What made you decide on this structure? Have you ever seen anybody do anything else similar?

CM: I had all the raw materials: my 30-year-old journal, letters I wrote to Mark 30 years ago, emails we exchanged during the writing, all my published work … it was very much like the way a jazz musician knows all the notes in the chords and knows his own horn and his range, so when he adlibs, he uses his raw material in the way it seems to fit and in the way it speaks what he wants to say at the time. In other words, there wasn’t a lot of pre-planning. Once I got rolling, or got further into the book, and certain patterns or motifs or stylistic rhythms had been made apparent, I more consciously used them. A very short answer would be to say I used the material the way it needed to be used, but the structure was also inadvertently created by a form of laziness: I didn’t want to retype the journal or those letters, the task seemed daunting, and I wouldn’t be able to stop myself from changing things. So I scanned them, and the structure of flowing the book’s text around the scanned artifacts was born (of availability in the technology). Some of the scenes from published fiction were included, at first, because I felt it was pretentious or fake to try to re-dramatize a scene I had already exploited in fiction, so I just included a scan of the page I the book where the scene appeared. Then I realized that how I had written the fiction said something about the me who had written it. So I started using the fiction excerpt for self analysis. With this technology so available to all of us now, yes, I have seen scanned artifacts in memoirs and even novels, but I think the reasons I used them are organic to my book.

BZ: I also read your previous book, Various Men who Knew us as Girls, which you quote from, in Something Wrong with Her. You’re making the point that throughout your fiction you are trying to work out some of the same issues you discuss in your memoir. The two male band instructors you worked for and you write about in these two books seem like a turning point in your life. On the one hand, you were being used in a power struggle between the two men in the department you worked for, and you wished you’d stood up to them more. On the other, you felt another teacher, older than you, wanted to have an affair with you, but that one of the previous two men you worked for stopped him, and that might have been the start of some of your sexual dysfunction. You didn’t know when you were younger that someone asked the older man to stop flirting with you but felt as if you’d suddenly become unattractive to him. Do you feel that you’ve worked these things through now by writing about them, or that they’ll always be factors shaping who you are? Do these sorts of dynamics still exist in your life?

CM: Those dynamics will always be factors in shaping who I became. Who I become from here on is being shaped by different factors now. It took a lot of books for me to feel “finished with” the bewildering experience of being in those two men’s power struggle, while also hero-worshiping one (and then years later discovering many of his principles were and are the antithesis of mine). I can’t feel the relationships are resolved, but only that I have come closer to understanding who I was to them and how it shaped who I was to myself.

BZ: In your memoir, you write, “Oh Mark what am I going to do when I finish this book? It’s the only life I’m living. How does a person who only lives while she writes, when she writes, in what she writes, write a memoir? It turns into a book that’s happening while she writes it. A life that ends when she stops? Am I playing Scheherazade, or is it like the fate of the narrator in my first novel, where she will cease existing when she realizes she’s been invented by her lover? Except, I already know I’ve been invented in all these books by only myself.”

The anguish in this passage really struck me. You seem so distraught over the idea of finishing this memoir, as if the character you’ve created of yourself on these pages really will cease to exist when the story ends. How did you feel when you finished the tale? Were you worried that the relationship you developed with Mark on the pages might not turn out to be real? Did you feel that a part of you was gone when the book was done?

CM: The possibility that the relationship with Mark, rebuilding as I wrote, would not last beyond the writing of the book was very real. During the writing he withdrew for a while. I think I finished chapters 14 – 17during a time when I didn’t know if I would ever have contact with him again. Then later, after contact was resumed and he was struggling with how to leave his wife — he moved out but returned to her in about 10 days — that was originally the book ended, right after he went back home in January 2010. The passage above was written in January 2010, but just before Mark’s first attempt to leave which ended in his going back. I’ve since heard these failed attempts to leave an unhealthy relationship are common, and, as it turned out, Mark left that situation for good in June 2010. Since I was still working on revisions and shaping the finished first draft, I added the very last chapter much later in the process to remove the confusion that it seemed the story ended with Mark returning to his wife. There are dated flash-forwards and emails distributed throughout the book that indicate the relationship is still developing after the January 2010 low point that had, at one time, been the end of the book. But I know following datelines in a book are difficult and many readers skim over them without following closely.

As far as the idea that the character of myself in the book would cease to exist … yes, very much a real feeling as I wrote, especially during the time when Mark had withdrawn. I was experiencing some predictable symptoms of depression, including suicide ideation, and writing the book — the me who was the real-time author as well as re-living vicariously the character of me in the past-tense scenes — was the only time I was functioning (or living). It was a difficult, dark time, from about chapter 14 through 24.

BZ: In the memoir, you talk about the modesty you developed when you were growing up—not looking at your own body even when you were in the shower. Keeping a towel over your body at all times when you were in the bathroom getting ready so you would never actually see your body. Always averting your eyes when changing clothes. I found this fascinating. Where do you think such modesty came from? To your knowledge, did any of your siblings develop behaviors like these?

CM: You say modesty, I say body-loathing. I have no idea where it came from. It is so common in American women, especially of my generation, but I have no idea the degrees of it in my sisters (nor in other people). The fact that you, a woman of my generation, asks this in this way tells me that my behaviors in response to it are a little extreme. Yet I had no problem wearing short levis cutoffs and a halter top to marching band rehearsals when I was 20. I didn’t mind looking at my muscled arms and perpetual tan

BZ: When you talk about the sexual dysfunction itself and how intercourse actually caused you a great deal of pain whenever you tried to have it, you explained some behaviors you had as a child that may have caused you to use muscles incorrectly which in turn could have caused permanent damage. For instance, you had the habit of never using the bathroom before you left school even though you needed to. By the time you got closer to home, you had to urinate so badly you had to contort yourself and reposition to prevent yourself from going. It was very compelling.

CM: The book explains that event this way, “On more than once occasion, however, while I crouched on the roadside — rocking, squeezing, squirming — fighting the muscles that were straining to relieve my bladder, there was a distinct, almost audible (although it wasn’t) snap, a pop, something came apart, something broke. My muscles were instantly lax. Pee flooded out of me. I could control no muscle to stop it. I know now the muscle that stops urine flow is the pelvic floor musculature. Those incidents somehow “broke” it. By the time my bladder was full again, that same day, I was holding my urine. I have never in my life — other than those times — been incontinent. But I can’t ignore these strange incidents concerning this same troubled muscle, and perhaps it was started in childhood, as Dr. Moldwin suggested, when he shrugged his shoulders over the causes of PFD. Maybe I didn’t damage the pelvic floor muscle into incontinence-causing weakness; perhaps I only confused it as to what it was supposed to be doing, and when.”

But it was only my hypothesis that these incidents damaged my pelvic floor muscles, becoming the physical reason for me to have painful intercourse as an adult. The condition — vaginismus — can have physical and psychological causes, and I do think I had the latter. But I couldn’t ignore these memories of something “snapping” as I tried to hold my urine.

BZ: You go on to talk about how biofeedback can help when the muscles have become tormented from being used incorrectly. Do you mind explaining a little bit more about how biofeedback works?

CM: Biofeedback means showing a patient, using something the patent can perceive in another way (usually sight), what is going on in her body or in the treatment. This helps the patient’s brain get in line with what is desired. The doctor I quoted said “The concept of biofeedback is to give the patient some visual information about a bodily function.” So the “feedback” was only for my own mind: I could see the graph being created by the electrodes attached to both my pelvic floor muscles and my abdominal muscles. So I could see when I tensed abs vs. when I tensed pelvic floor muscles, so I learned (almost instantly) how to tense one and not the other. That way I learned how to do the exercises most effectively. I could also see, right there on the screen, some sharp spikes suddenly appearing, even when I didn’t feel anything. The practitioner told me those were muscle spasms — the things that caused sex to be painful. I hadn’t known I was doing anything, so I could understand the nature of the problem. The biofeedback itself was not a treatment, except that it taught me which muscles were in question, and how to isolate them in the exercises. It only worked to a point, though, because (a) the exercises must be maintained forever, and (b) the exercises can’t overcome the basic psychological reaction to anticipate and fear pain, thus (in the case of sex) causing pain.

BZ: I found myself feeling, as I neared the end of the book, that the greatest intimacy in Something Wrong With Her wasn’t actually the sex, but the fact that the reader is so close to the narrator and her man as this budding romance develops. I realize Mark and you have known each other for a very long time and that your feelings were such that something could have happened earlier, but didn’t. Did it make you feel vulnerable to share letters going back and forth between the two of you as your romance was developing? Did you ever fear jinxing it? Did it bring you closer to write parts of the book together and to develop a “duet,” which you and Mark now perform with reading and sax playing?

CM: Mark’s involvement with writing the book came, at first, without his awareness, as I was using his emails. (I didn’t even consider the questionable ethics of this!) That did not make me feel vulnerable. At that point writing the book was only a personal journey and I was going through my darkest days. Preserving the emails, selecting and positioning them to mean something, so I could look back to understand what was happening, was all I was feeling. Nothing I did in the writing I was doing was going to jinx or change anything that was (or wasn’t) happening in real-time during the writing. It (writing) was only a way for me to keep going through that time.

Later, Mark’s involvement also came without his realizing, when I gave him portions to read, and then started to insert his reactions to certain passages. He was giving another perspective, both by virtue of him being a different person in the same scene, and by virtue of how much time had passed since the scene occurred. It added a time-layering that deepened the book (and of course make it not linear enough for a commercial press). Naturally he started to know I was doing this when I would show him the revision. He never once said “Hey, don’t include what I wrote.” By the time we were doing this, he’d gotten past most (not all) of the trauma of leaving his unhealthy relationship, so nothing we did in this book threatened what was happening between us. He also seemed to want the world to know. The saxophone-and-reading duet we do in bookstores is an extension of that as well. I guess because he had been hiding his feelings for 25 years, carrying on a secret relationship with just his memories of me in his head, he was ready for that to break out in every way imaginable.

BZ: I appreciate your thought-provoking answers, Cris. And it’s really an interesting book on a topic we don’t get to read too much about.

Leave A Comment