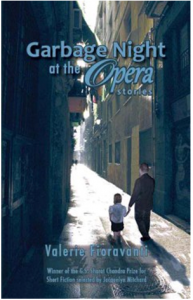

The seemingly romantic way in which Valerie Fioravanti connects her stellar collection, Garbage Night at the Opera, is by placing all of a large Italian family in the same Brooklyn apartment building. Through this ingenious yet natural connection, Fioravanti’s characters move out from their families when they’re of age and get their own apartments—in the same building. Aunts, cousins, brothers and grandmothers live down the hall or upstairs or downstairs to maintain their own little community. However, as any one of these extended family members can tell you, it ain’t all that romantic, and therein lies the conflict and tension of this highly-engaging and beautifully-written book. Just ask Franca or Angela or Rose Anna, especially Lina, or any of the other provocative characters in this award-winning collection if they think it’s always a great idea to have family quite that close by. The answer isn’t hard to predict.

Family drama and romance abound in this literary collection, but the history of the area is equally interesting. The family doesn’t seem to

The title story, “Garbage Night at the Opera,” is heartbreaking and exquisite. Massimo, the sole parent of Franca after her mother has died, is proud, attends college three nights a week in bookkeeping, and always wants to improve himself and especially his daughter. He’s found inexpensive student tickets to take Franca all the way into Manhattan to see La Bohème. When she gets home from her grandparents’ place, two floors down, he’s already ironed her dress for the opera, and when she asks if she can wear a different one instead, he only wants her to be happy. Their journey into the city is one of high-class distinctions, the haves and the have-nots, finding vast treasures on the street when it’s garbage night in Manhattan. He can hardly bear for Franca to be hurt as her innocence is awakened during run-ins with Manhattan garbage owners who think they know how to raise his daughter better than he does.

In the poignant “Earning Money All Her Own,” Angela has decided on a different career move than the rest of her family. Rather than working in a factory or one of the breweries along the river like the rest of them, she decides she wants something different and takes on the far more elegant job of a switchboard operator at an answering service in Manhattan and commutes. She has four sisters, three younger, one older, but Angela is the only one with a savings account. She gets her hair done professionally, goes to out to lunch and movies with her girlfriends, though her sisters “didn’t have time for such foolishness.” She even walks along streets at night without another woman anywhere near. Here the sisters think she is “too adventurous, and according to them, this was the reason she remained unmarried (as if single men only lived in Greenpoint and Williamsburg).”And yet when one after the other of her brothers and brothers-in-law lose their jobs, mostly at the brewery, and they fall into dark depression because this is all they’ve ever known, it is Angela who has money to loan them and brings them meals. It is Angela who takes care of them and endures the sad endings that come to some of her family members.

In “Make Your Wedding Perfect,” Lina, until now a good Italian girl, is bombarded with wedding advice from some old bridal planner: “The most important decision you make may be your dress. The bridal gown sets the tone for the entire wedding. Choose carefully, brides!” And later: “A bridal shower honors the bride and allows her friends and family to celebrate her good fortunate, as is fitting, with attention and gifts. Prepare to be surprised, brides, unless you want to be immortalized in wearing sweatpants and a hat made of bows and ribbon!” Only two stories later in the collection, the reader is shocked to hear what becomes of Lina.

Occasionally one might wish for some more sympathetic male characters. Fathers, sons, brothers, and lovers can be pretty cruel, both emotionally and physically. However, there’s the wonderful Massimo in the title story who so lovingly dotes on his daughter. And these are tough times. The men, expected to be the breadwinners, are being torn from jobs they expected to do their whole lives. They’re losing their identities as longshoremen, factory workers, beer makers. And therein lies the artistry of this book. The gritty, sticky feel of living by the shore is brought home as if you’re living there, too, as is what it would be like for your sisters, mother, daughters, and wife—no matter how much you loved them— to be able to watch every last thing that you do, especially when you’re down on your luck. The utter realism and stunning lyrical writing in Garbage Night at the Opera makes it a must read.

First published in Gently Read Literature

Leave A Comment